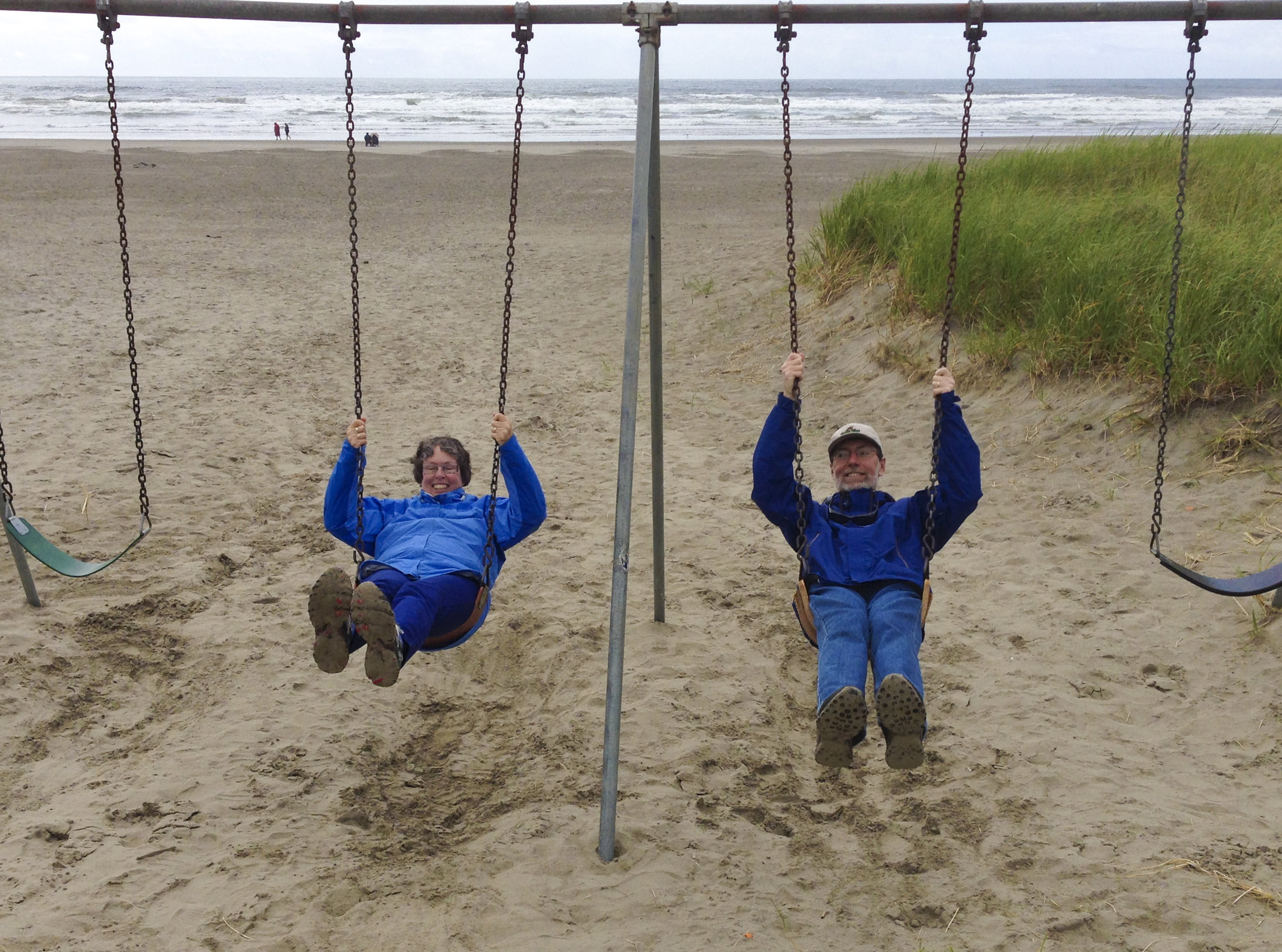

The Seaside Swings

Chilled air swept across dark sand, choppy waves, and tall grass spread atop the dunes of Seaside’s main beach. I remember the Coho Ferry from Victoria, British Columbia to Port Angeles, Washington foreshadowing this type of weather, though a laughter-filled drive five hours south brought our mood back to holiday mode.

My parents and I road-tripped to the Oregon Coast in search of mid-June sunlight, but instead pulled Gore-Tex jackets over sweaters and pants. Despite the frosty breeze, we ventured onto the wide beach, left flat and empty by a low tide. Mum stopped to pat dogs that streaked along the sand chasing tennis balls, and sparked conversation with their owners about her Carly back at home. The running joke was she had stopped so many pups for a scratch that Dad took a photo of her patting one — part of the Meriwether Lewis and William Clark bronze monument with their dog, Seaman.

We snapped a family selfie as lips shivered, and hat hairs sprouted in all directions. Then striding back up the beach in search of a windbreak, we saw it. In an area between the sand dunes, almost hidden away from the rest of the beach behind long green grass, four chain swings dangled from a tall metal frame. I said it might make for a funny photo if they got on — something to remember our trip by. They agreed. Mum and Dad sat down and pushed off, toes pointed up as they kicked out. They smiled, but struggled at first to move in unison. I held my phone up for a photo.

My parents had soared across the Pacific from Australia to see me graduate, and we turned the trip into a drive south through the top two northwest States. As a high school math teacher and spare time knowledge sponge, Dad had agreed, for the first time ever, to take a vacation not planned out from start to finish. Let’s just drive down there and go with the flow, I told him. You have enough to deal with already. To my disbelief, he complied, but was still armed with an assortment of Washington and Oregon maps to ease the decision.

With my undergraduate degree completed, this would likely be our last time in the Northern Hemisphere together. After 24 years full of trips to visit Mum’s family in Vancouver and Prince George, it seemed strange that Mum, Dad, and I may never be back. We probably wouldn’t cross the Lions Gate Bridge to where her parents had lived in West Van, or marvel at snow during a white Christmas in northern British Columbia as a family again. After five years abroad, I was spending one more year in Victoria, then returning home to them in Canberra, Australia. We didn’t know how much longer Mum had left.

Mum’s short-term memory is almost gone and her old stories that convinced me to travel, see some changes each time she recites them. But she and Dad still make each other laugh, which is enough to keep them going.

I played Australian artist, Chet Faker’s debut album through a short white auxiliary cord plugged into my iPhone. The soulful, keyboard-heavy rhythm matched the leather interior of our brand new Chevy Cruze, and created a sense of class like a cocktail bar. It swirled through the body and soothed the mind. Compared to my parents’ old Mitsubishi and Toyota Prius back home, this car not only harboured elegance, it had 138 horses under the hood. Unfortunately for me, I was two months too young to test out the rental, a devastating detail in the fine print.

We drove around the western side of Puget Sound, looking out across the Salish Sea to a summer snow-topped Mount Rainier. Spending a night south of Olympia in small-town Chehalis by the I-5 freeway, we then left the highway and went west en route to Gearhart By The Sea.

The Astoria Column stands eleven and a half storeys and is covered in copper-coloured murals of the region’s historic events: Captain Robert Gray’s discovery of the Columbia River, the end of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and the arrival of the ship Tonquin. The grassy hill and paved parking lot around the column overlooks a spattering of houses, met by the Astoria–Megler Bridge, which crosses the mouth of the Columbia River. The bridge looks like a miniature, insect-green, Golden Gate Bridge, only it tails down halfway into a lower jetty-like structure — as if a dinosaur is merging either side of the vast body of water.

Climbing the 164 steel-grated steps up the inside of the column, my hands dripped with sweat. I’m scared of heights, and that stupid family lookout had me terrified. We walked out onto the viewing deck and wind burst against us like a swift damp push into the tower’s concrete walls. Mum stood by Dad, completely unfazed and enjoying the river view. I retreated to the other, wind-protected, side and hugged the column for dear life. Mum asked why I wouldn’t come to the railing, forgetting my passion for sea level. She continued to take in the mountains. I sprinted down the stairs.

She loves taking photos of anything, but particularly flowers, trees, and plants. Mum has a real eye for detail on houses and landscapes we pass that I don’t remember her having before. Maybe more time avoiding repeating questions forces her to focus on other senses.

“Do I have time to take a photo?” Mum asked as we pulled up in front of a gas station and diner, looking for lunch.

“Yep,” Dad and I both replied.

“That might be the most beautiful flower basket I’ve ever seen,” she said.

Her eyes shifted from the basket outside the passenger window to her lap. She felt down by her feet, twisted to see the back seat, and fumbled around inside her purple backpack by my leg.

“Do you know where I put my camera?”

“Is it in the glove compartment?” I suggested.

She fiddled with the catch of the unfamiliar Chevy until the cover popped open, then grabbed her Canon with a sigh. Signs of early-onset Alzheimer’s started with forgetting an item on the grocery list when I was a teenager, or losing her car keys around the house. From there it advanced to misplacing the car in multistorey parking lots or forgetting she had driven to the local shops and walking home. Mum was diagnosed with the form of dementia at age 61 in October 2012. I found out over Skype.

Even if it’s just a photo of an average pine tree by a golf course at our hotel, or a basket of flowers across from Kiwi’s Fish & Chips where we ate lunch, she doesn’t care. She’s sometimes slowed down by hitting the “power off” or “view photos” button instead of capture, but the little Canon in its attached leather case keeps memories on file that Mum can’t.

Everything in Mum’s life is now like a pendulum that sways like the Seaside swings to find the right balance. How often she tries to work her short-term memory versus how often she resorts to telling stories from the still mostly intact long-term; how much Dad can help without making her feel incapable; how many days, weeks, or months she will still recognize me.

Mum and Dad stayed in Victoria with one of Mum’s best friends from high school. Nancy’s husband was a retired Times Colonist newspaper editor, and they gave me my first Moleskine notebook — a classic black one — and a fancy pen as a grad gift. I sat in the upstairs loft of our character beach house in Gearhart, Oregon and wrote. I wrote and I wrote, walking out onto the balcony and listening to the silence of people sleeping over a roaring Pacific Ocean. Beaches in B.C., for the most part, have flat, calm ocean, and the change in swell was a welcome one. The sound reminded me of Alexandra Headlands on Australia’s Sunshine Coast where my grandparents live.

I thought about how I continually pushed my limits to maintain a high-strain environment since Mum’s diagnosis. I took five classes at two different schools, commuted between three campuses, worked an internship, and played varsity basketball four hours a day, six days a week. I found peace in maintaining an unbearable workload because it pushed the local stresses to the front of my mind, making the bigger trauma of Alzheimer’s less daunting. Awake until four in the morning writing papers after three hours of basketball was better than free time. Moments alone and unoccupied filled my head with words I might say at Mum’s funeral.

I’m starting to realize the little stresses are minor. Maybe I can learn from Mum’s camera and remember the things that seem beautiful at the time. Everything else can be forgotten. Right now what’s beautiful is my parents when they laugh or hug.

I had seen my parents be playful before and laugh about stupid things, but on those swings it really felt like they were just letting go and living in that exact moment. They kicked out and found a connected stride in unison; each swing higher, as exhilarating as the Easter Weekend they met camping on Australia’s South East Coast. The tensions that sift through any marriage like long hours at a job you don’t love, keeping a kid content, planning after school activities and lunches, and dinners. Anxiety. Depression. The jigsaw pieces that jiggle apart many marriages stayed stuck together by my parents’ ability to make each other laugh.

Though this moment on the swings wasn’t like laughter and a hug in the kitchen or flinging a tennis ball for our spaniel-poodle cross, the stresses of early-onset Alzheimer’s magnify the joys of each moment of clarity. At Seaside Beach there were no doctors, no Alzheimer’s Australia guest speakers, no guesses at how many months or years we have left together. There were just two grown up kids seated on the Seaside swings, and their boy taking their picture.

This story was originally published by Island Writer Magazine